Roman Pottery

Roman pottery underwent a great deal of evolution. A growing population meant a need or mass production of Amphorae, coarse ware and fine ware. New techniques of decoration were continuously developed. Wealth and access to materials like metal and glass meant that ceramics no longer held the earlier unique position. Given the right location it is not uncommon to find Roman pottery sherds plowed in the the ground. These can be analysed according to a number of very basic features such as material, shape, surface decoration and if you’re lucky a stamp to say where it was made.

READ MORE

Ancient Roman pottery can be analysed and studied through a number of clues and features:

Roman pottery (earthenware) can be generally split into three main areas of use and decoration:

This was particularly the case in Rome itself, where wealth grew to the highest level. The fine ware pottery market remained stronger in other parts of the empire and with time Gaul became an important and artistically influential production centre.

The range of Fine Ware pottery shapes is obviously dictated by its use: as special showcase pieces, as vessels for cosmetics or to be used on special occasions and dinners. Of course, glass and silver were particularly suited to these areas of luxury merchandise just as they are today. The influx of glass and silverware negatively impacted the range of Fine Ware pottery and the range of shape and form. In fact, there is evidence of shapes which evolved as a consequence of glass-making which were then copied by the potters. For example, there’s a second-century pear-shaped jug with relief work in the British Museum which is extremely similar to earlier first-century glass work. Another example of glass making influence on pottery includes a faceted surface rather like cut glass facets on goblets and round vessels. This tendency more or less dates to the fourth century.

As a result of this, the level of roman fine ware pottery was relatively basic with its prestige eroded by a tendency for mass production. Painted artwork on Fine Ware pottery was reduced to geometric patterns and designs. The appeal of “fine ware” was limited to craftsmanship, shape and surface texture.

A possible exception to this is what is known as Arretine work, made in potteries at present-day Arezzo, near Florence in central Italy. In this case, the figurative painting on the pottery surface was replaced with actual sculptural relief work which could be stamped in molds and applied to the surface of the vase before painting and firing.

In contrast to the Greek love for a black glaze, which allowed the artist to preserve the natural red ground as a base colour for expressive artwork and figures, the Romans developed a preference for a unified red, shiny, glaze which lent itself well to the relief figure decorations.

Arretine pottery was widely appreciated across the Mediterranean and was imitated in pottery centres across Italy, Asia Minor, and Gaul, so much so that its production more or less shifted to Gaul.

On a more modern note: The industrial revolution of the 19th century allowed the Arretine result to be copied and mass-produced in England by potters such as Wedgewood. It remains extremely popular even today.

The work of southern Gaul imitated and took over the Arretine style and by the middle of the first century made it its own. Gaulish produce was generally heavier and with a higher gloss finish. Some fifty years later Gaulish work was superseded by the work of North African potteries which also produced red wares although the finish was generally less glossy or even matt. The general term for it is “African Red Slip” or “ARS”.

This meant that the clay used was less refined and included rougher (coarse!) inclusions and impurities. The walls would tend to be thicker in order to make the wares more resistant to kitchen use. From a materials point of vie, it is likely that the inclusions would make the wares more likely to break and therefore also contributing to a need for a greater thickness of clay.

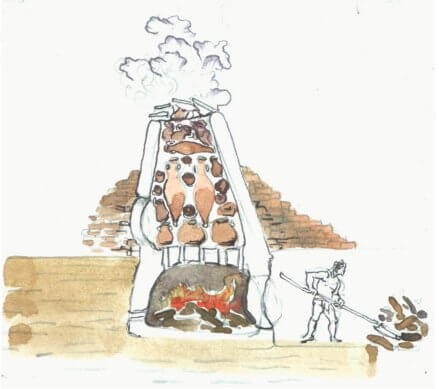

Firing was less careful and generally done in a closed furnace, which would tend to consume less fuel. The “reducing” atmosphere in these ovens ie smoky and short of oxygen, tended to make the baked clay go brown/black in colour. Darker patches on the earthenware surface would also arise where one pot touched another in the furnace.

The general size, weight, finish and shape of coarse ware was strongly driven by the utensil’s intended use. Pots for storage, cooking, eating and so on all had their particularities. A rough grain surface on a plate intended for semi-liquid poultices would hardly be impermeable and certainly not easy to clean! A “slip” would generally be used to provide a smoother finish when required.

I think we all know what an amphora looks like and plenty of them have been found under the sea in the remains of cargo holds of sunken ships. Superficially we would tend to classify Roman amphorae in a single class of shape which allowed them to be easily stacked in a ship’s hold (which wasn’t square!).

In reality, amphoras have a large variety of shapes and sizes. The different shapes and features on amphoras were strongly tied to the location of manufacture, type of produce to be carried and the year(s) of manufacture. Just to give a feel for what I mean: a “Haltern 70” is not a type of gun but a type of amphora, produced in Spain. It is tall and cylindrical with a collared rim, a spike at the bottom and grooved handles. The surface texture is rough. A “Dressel” amphora on the other hand… You get the picture.

The systematic study of shape and makers’ stamps has helped archaeologists to define a clear picture of mercantile trade routes. In Rome itself, there is a whole hill called “Testaccio” entirely made up of the millions of shards of amphoras used to import goods. Given the difficulty of eliminating earthenware waste dedicated workmen were employed to lay the shards in progressive layers. Monte Testaccio is now covered in trees and parkland but various areas have been excavated and “revisited” as veritable geological layers of mercantile history.

We have collected further information and images about Roman Amphoras on a separate dedicated page.

The manufacture of Roman pottery was much the same as that of other civilisations and in fact pretty much the same as it is today.

roman pottery was made by one of four methods. Methods could also be combined.

Roman pottery lacked the intricate painterly decoration loved by the Greeks and Etruscans. The most common form of decoration was through a simple “slip” painted over the surface of the pot before firing.

A slip is a thin watery slurry of refined clay which fills and smoothes over any coarse gaps in the pot’s surface. The benefit is great both aesthetically and in terms of practicality given that the pot is rendered more impermeable and easier to clean.

The slip could be rubbed over with bone or wood so as to align the particles into an even smoother burnished surface or polished to a glossy shine by rubbing it with a fine abrasive such as ash. The slip itself could be made of a different type of clay so as to give a different colour although excessive differences in the material’s properties could lead to cracking or peeling of the surface.

The colours tended to be either blue-green or light honey brown although other colours could also be achieved. The technique relied on combining metals such as silver or copper with lead salts, which provide a melting point low enough to be reached in the firing oven.

These powders could be sprinkled onto the surface of the pottery or even suspended in water and painted on. Copper gives a strong green. Ferrous (ie Iron) compounds tend to go red or brown. The method of firing is important and the result is affected by temperature and amount of oxygen present in the oven. It seems that the famous black ware made by the ancient Etruscans known as “Bucchero” was achieved, at least in part, through firing in oxygen-deprived atmosphere.

At its most basic, relief work could be much the same as we seen on tribal African wares nowadays: with various geometric patterns or bumps or grooves and so on. At its best, the Romans had a strong taste for a figurative shallow relief which might either be made with a mold and applied to the surface of the pot or alternatively which could be drawn directly onto the surface by squirting a semi-thick clay through a nozzle, a little like toothpaste.

The Romans developed the art of glass making to an extremely high level of craftsmanship. Before that glasswork depended on an opaque translucent material known as “glass paste”. During the Roman epoch, the purity of glass was greatly improved and the inclusion of definite metal impurities allowed manipulation of its colour and translucency. This material was used to make wares of different shapes and sizes with relief sculpture in the classical style.

This form of art was extended to the production of true artworks in the form of glass tablets with sculptural relief of figures and mythological events much in the same vein of cameo work done on shells or Aretine pottery ware.

Further extensive information regarding Roman Glass and pottery has been collected on a dedicated page about Roman glassware.

Designed by VSdesign Copyright ©Maria Milani 2017

Please email us if you feel a correction is required to the Rome information provided.

Please read the disclaimer

"Ancient Rome" was written by Giovanni Milani-Santarpia for www.mariamilani.com - Ancient Rome History

Designed by VSdesign Copyright © Maria Milani 2017